Westward Bound: From Classroom to Catamaran

A gale hammered our boat for weeks between Bora Bora and Niue. The steering components were failing, our stamina was waning, and the shattering wind was forecast to continue for days. At some point, nursing my wave-blasted boat through the darkness, I struggled to retrace the sequence of events that led up to this moment.

I had met the boat’s skipper, my wife Miranda, while teaching in Colombia some years earlier. She had been working at Colegio Jorge Washington (COJOWA), a charming little school not a stone’s throw from the Caribbean, for a year before I showed up. COJOWA was our first venture into international teaching, and Colombia was a great place to be twenty-something. Teaching in Cartagena introduced us to a cadre of colorful expats, each with intriguing histories. We loved the unique travel opportunities of Colombia, and the passion restored in our teaching careers, especially coming from the U.S. public school system where teacher burnout was tangible.

Miranda and I had separately moved from the Midwest to Colombia to slake our wanderlust. After six months of teaching math side by side during the day, kitesurfing together after school, and dancing salsa into the night, there was nothing more to talk about besides where our adjoined path would inevitably take us.

After a few years in Cartagena, we felt the itch to experience a different part of the world together, so we went to the Search Associates international school job fair in Boston. It was interesting to go as a teaching couple, as opposed to our previous experience as individuals. The whirlwind weekend wasn’t as daunting with a partner, as we could play to each others’ strengths during interviews and weigh decisions as a team. At the same time, the choice of schools was more limited since we needed suitable positions for both of us.

Any experienced international teacher will tell you that job fairs never go exactly as planned. We’ve always ended up in different parts of the world than initially intended, but we chose schools for the right reasons and have always had overwhelmingly positive experiences. Leading up to the fair, we were set on moving to a new continent, a sentiment that was eventually overwhelmed by an offer from a fantastic school in Santiago, Chile. It was pivotal that we remained flexible at the job fair as moving to Chile and working at the International School Nido de Aguilas was absolutely the best decision for us.

During our four years at Nido de Aguilas, we flourished professionally under amazing leadership and with colleagues at the top of their craft. Personally, we continued to learn new adventure skills including mountaineering, climbing, backcountry skiing, and paragliding all the while in an environment where nature was untouched, unstructured, and uncharted. In truth, there was no real reason to leave South America. The welcoming nature of the Chilean culture fostered many local friendships and made it easy for us to feel integrated. There was always plenty to explore out of school, and we grew professionally like nowhere else we’d worked before.

Well before Miranda took center stage, I knew there was a deep-seated requirement in me to embark on an adventure that would legitimately test my limits. I wanted an extended, unsupported expedition that pitted me against an age old adversary: the elements. The concept of sailing around the world formed itself out of those requirements. The idea was to amass a lifetime of skills and resources to apply towards the goal later in life. I shared as much with Miranda on our first date as a spoiler alert. But a few years later after getting engaged, she suggested we attempt the boat trip sooner rather than later. The caveat: two years only and the plan had to be bulletproof. Miranda is logical and organized, and wouldn’t deign to shoot from the hip for such an undertaking. So the planning began!

The details took about a year to iron out and for several months ran concurrently to organizing a fabulous wedding. First and foremost, did we have sufficient funds to undertake the venture? Blogging is common among cruising sailors and many are open enough to share their alarming expenses online. It was a goldmine to work with. We didn’t want loans or financial help but calculated that between Chile’s low cost of living, our fairly frugal lifestyle, and excellent savings potential at Nido de Aguilas the trip was financially possible.

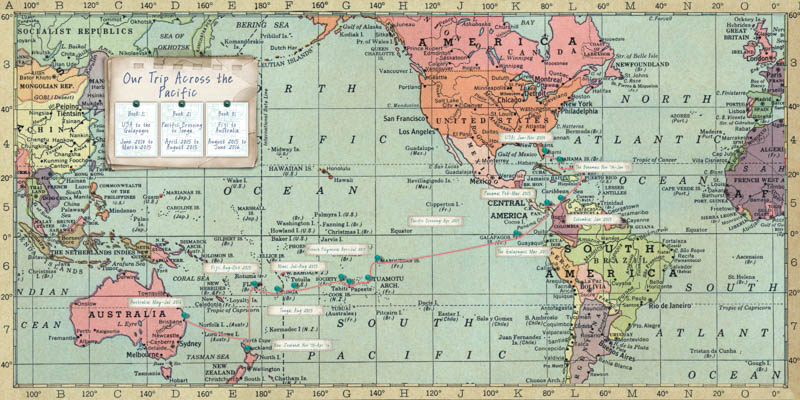

Second, where we would sail? The bragging rights associated with sailing all the way around the world are second only to summiting Mount Everest or exiting the atmosphere. It’s what I had my heart set on, but we came to find that a circumnavigation in two years required major compromises to our goals for the trip. We desired solitude and the confidence that comes with crossing endless stretches of open ocean, but just as important to us was having time to freely explore above and below the water. The obvious became clear: we’d sail the Coconut Milk Run, a route going across the Pacific from the Caribbean to Australia.

The next question to be answered centered around the sailboat itself. We decided on a 38-foot catamaran, the Lagoon 380, as our top choice. Catamarans are more expensive than similarly equipped monohulls, but we deemed their merits invaluable for Miranda’s introduction to sailing. Did I mention that she didn’t know how to sail yet? I grew up sailing on Michigan’s Great Lakes, but Miranda did not. She was raised in a dairy farming community of Wisconsin, so while she lacked nautical experience, she was no stranger to getting dirty, working hard, and living simply. Expat Midwesterners often have much in common, and in this case our upbringings cultivated a daring spirit and can-do attitude in the both of us – perfect for such a crazy idea.

Chile’s proximity to the Pacific allowed us to take sailing lessons while still working. Despite our initial disparity in sailing experience, we started our lessons together as beginners. This made the learning experience something that we did as a couple, always together, which meant it wasn’t just about learning vocabulary and technique, but also about growing together as we became more and more excited about the adventure to come. We later graduated to more cruising-focused courses on Lake Michigan, all the while scouring blogs of sailing ventures and taking volumes of notes.

A significant leap of faith was involved in the next step. Not every detail could be planned for, which left Miranda feeling anxious. Living abroad taught us that although we couldn’t prepare for every contingency, we did possess the problem solving skills to react to obstacles in real time. However, this trip would be more demanding than anything else we had ever attempted. During uncertain moments like these, it’s human nature to try to control the situation, and like many overachievers Miranda does this by overplanning. Letting go of this need and being confident in the ability to overcome unforeseen challenges was, by her own admission, Miranda’s single greatest area of growth, although I’d say her evolution into a wicked freediver was far more impressive. Courage often comes in recognizing and acting upon opportunity. We knew it was time to go sailing.

When the school year ended we flew to Florida, set up shop in a friend’s empty vacation house, and got to work. And good gravy was it a lot of work. We drove around southern Florida for a month to check out dozens of boats before finding our Lagoon 380. We named her Tayrona after the jaw-dropping national park in Colombia where Miranda and I kindled our first spark. Tayrona was ten years old so prior to setting out we spent a month updating her systems in Miami. Our itinerary revolved around extended blue water sailing so no expense was spared on offshore equipment. Safety at sea means a strong boat, but also current weather forecasting and communications. Tayrona was outfitted with wonderful new toys like long-range single side band radio, electronic chart plotter, and radar to cut through rain and darkness. Energy independence was priority, so we added and improved the solar, hydro, and wind generation systems aboard until Tayrona could be powered with renewable sources alone.

Before the trip I knew my way around a boat, but I was floored by the quantity of information we both had to learn before we could confidently set sail – marine technology, mechanics, plumbing, electrical, and not to mention each country’s bureaucratic red tape. The quantity of knowledge we had to ingest in preparation for such an adventure was astronomical. To be a good teacher one must remember what it’s like to be a learner. Some teachers go back to school for their Master’s; we got our further education in engineering, logistics, and oceanography. It was money well spent.

We set sail for the Bahamas after hurricane season ended in the Caribbean. There, in the sandy and forgiving shoals we cut our cruising teeth, honed our sailing abilities, and learned volumes from seasoned sailing friends along the way. We brought the average age of the sandbar parties down by at least fifteen years, but our nautical compatriots had an innate desire to help out ‘the kids’. We milked that know-how cow for all it was worth.

We sailed our first long passage south to the shores of Colombia on a rowdy beam reach with plenty of cargo ships to dodge and even a dicey drogue deployment to keep us from surfing down waves. Watching the silhouette of Cartagena rise from the sea was well worth the beating, though. The city presided over many significant moments in our lives and seeing her again left a lump in my throat. After visiting our old haunts, we made passage for Panama. The Islas San Blas bid us welcome, and we explored the scattered iconic islands for a week before getting down to the business of crossing the Panamanian isthmus via the famous canal. We waded through the appropriate bureaucratic quagmires and eventually secured our little boat a transit time slot. A week later, with my parents abroad to line-handle, two other sailboats were lashed to Tayrona’s gunwales and we made our traverse through the jungle-encrusted bridge between the continents to Panama City.

Our days of waiting for an optimal weather window were a blur of activity as we prepared to traverse the long, uninterrupted expanse of the Pacific ocean. Provisions were frantically loaded into the boat literally by the wheelbarrow. Emergency equipment was checked and rechecked. Temperamental engines were fussed over. Then the forecast was clear and it was time to go. My sister and her husband came for the long push and together we slipped our mooring, waved goodbye to our parents ashore, and sailed off into the sunset. For real. It took about ten days to reach the Galapagos where we made some light repairs and re-provisioned. We must have bought all the eggs and tomatoes on the island. There was no real time to be a tourist; our visa limited travel between the islands and we needed to keep moving. Luckily, we had already visited the Galapagos before so we spent most of our time preparing for what Miranda perceived as the scariest part of our journey: The Pacific Crossing.

We sailed in radio contact with a group of other renegade sailboats to compare weather conditions, support each other in times of trouble, and also just to chat. The weather was mostly kind and the twenty-four days of unbroken horizon passed pleasantly. There is a sense of peace you can only achieve with days on end, uninterrupted, to fixate on a single task. I thought that we’d be dogged by boredom, but in fact I grew increasingly content to follow my meandering thoughts while scanning the endless blue. I especially loved night watches out on deck with the wind, stars, and spray, alone with my boat and my thoughts.

It wasn’t all rainbows and flying fish though. We listened in on the radio net as a sailboat slowly sank two hundred miles ahead of us. The crew was picked up by fellow cruisers and spirited tearfully to French Polynesia. Tense times occasionally washed over Tayrona but we fixed, fished, and figured out everything that we needed to. Frankly, there wasn’t any other option but to draw on all your skills, think problems through, and never give up. The morning we made landfall when the dark walls of the Marquesas Islands peeked out from behind sheets of rain I felt unexpectedly melancholic that the passage was over. It was with a profound sense of accomplishment that we pulled into the rolling harbor at Hiva Oa, nodding to the other ocean going captains as we anchored, and letting the forgotten scent of earth wash over Tayrona.

This is the point in the trip where we began to truly relax, be confident in ourselves, and realize how much we were enjoying the adventure. We had mastered the boat and her systems and had covered the largest stretch of unbroken water one could conceivably cross. We were sailors. We let go of the “what if’s” and trusted in our own abilities. Color returned to our knuckles. The Marquesas were enchanting with steep, fertile peaks plunging into secluded anchorages. We traded fishing lures and neosporin with locals for armloads of papaya and pamplemousse.

We played pinball with Tayrona through the archipelago for a few weeks then made a short passage to the Tuamotus, a group of coral atolls only a meter or two above sea level. The bluegreens of the lagoons were inexplicable and exploring beneath the waves was a highlight of the trip. The Tuamotus also had the densest shark population I’ve ever seen. No kidding, in any one dive we would see thousands of sharks. The endless visibility didn’t help. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that you could see sharks several kilometers away. I cannot overemphasize how many sharks there were.

Sunny weeks passed quickly in the Tuamotus and soon we made passage to the Society Islands which are mountainous and ringed by vibrant coral reefs. It was Tayrona’s first dock and city for many months and we found ourselves overwhelmed by being amongst so many people again. There were Polynesian dance festivals, pearl farms, and most exciting of all, marine repair shops. French Polynesia impressively spans a swath of ocean that’s the size of Europe. We didn’t expect to spend three months there, but one could easily explore for years without exhausting its supply of stunning anchorages.

Our next country, Niue, conjures up some of the most intense emotions from our entire journey at sea. After leaving Bora Bora we planned to sail a week to the Cook Islands, but as we approached a gale enveloped us. Entering the inlet to the only harbor would have required running a narrow channel that at the time was churning in the heavy sea surge. Trying to make landfall would have been lethal. It didn’t take long to weigh the options, and we left the boiling inlet astern, continuing west in well over thirty knots of wind and massive waves. We were uncomfortable, but overall it was the safest choice for Tayrona and her crew. One piece of equipment that hadn’t been replaced yet was our autohelm, the electronic responsible for steering the boat. The geriatric equipment finally failed in the six days of relentless winds, and we were forced to hold a course at the helm with a good old fashioned compass. Steering a boat by hand in heavy seas takes more focus than driving your car on the freeway, and clenching the wheel for hours on end felt like a never ending pilates class. We alternated three-hour shifts for five days. When not at the helm, we fixed equipment broken by the pounding conditions, made food to pass up to the helmsman, and tried to get some shuteye below. It was a long, cold, hungry stretch of water. I don’t think I changed clothes or brushed my teeth that week. When we pulled into the relative shelter of Niue, a tiny coral rock in the middle of nowhere, we were exhausted, downtrodden, and ready to call it quits. We anchored, made our first hot meal in days, opened a long-reserved bottle of rum, and sat down to spit vehemently about how stupid sailing really was. Just as we tucked into our plates, a pod of humpback whales surfaced mere feet from Tayrona and blew spray across our decks. The message from Poseidon was clear: stop wallowing and find positives even in wretched situations. During our stay in Niue, it was something of a religious experience for me to be in the water with these giants and well worth the trying experience to get there.

After a week in Niue with the whales and a week back at sea with a repaired autohelm, we found ourselves in Tonga. While in Tonga I had the opportunity to help a family repair the boat that their lives revolved around. Living on an isolated island, the family had no tools to fix the offending outboard, but dad volunteered his boys to assist me in tearing apart the engine. When I realized they spoke no English the teacher in me kicked in and I employed my best hand gestures and sound effects to try to teach them why the motor wasn’t running. They caught on quickly and our many hands made light work as we tinkered away in the Pacific swell. In thanks, the family invited us an incredible dinner, humbling us with their hospitality. My inner educator was tickled to be able to give those kids the metaphorical and literal tools to tackle problems in the future.

At this point in our journey the five days of open ocean on the passage from Tonga to Fiji seemed like a breeze. Fiji was glorious. There was sufficient infrastructure to aid cruisers but a multitude of secluded islands in which to get lost. Each island was inhabited by a tribe to whom visitors ceremonially presented kava, a potent root that the chiefs chanted over before brewing into a strong drink. The bitter liquid made your tongue tingly and turned the edges of things wibbly when excessively imbibed. There were manta rays, warplane wrecks, and submerged caves populated by blind eels. It was our last tropical country so we tried to soak up the idyllic anchorages and stunning underwater scenery.

After a few months in Fiji, we fled to New Zealand to wait out the hurricane season. It was a long passage with strong headwinds, but by that point we were confident sailors and knew we’d arrive safely with persistence and patience. It felt almost odd to be back in the first world, but the craggy coast never left us wanting for isolated places to explore. We learned to catch scallops and mussels. The fish were so plentiful that at times they made the sea boil.

In February we moored the boat in a well-protected inlet and flew to the London Search Associates job fair. A two-year gap on one’s resume is a legitimate worry, but our experience on the open ocean undoubtedly made us better educators and more competitive hires. The skills we added to our toolkit strengthened us as individuals and as a couple. We gained a wealth of experience to bring to the classroom and found a renewed empathy that comes from being a learner again. We can undoubtedly model perseverance, risk taking, and pursuing dreams, all characteristics encouraged in international students. The recruiters agreed, and we ended up accepting positions at the International School of Zug and Luzern in Switzerland. With the end of the sailing journey sadly in sight, it was comforting to have secured a future in an exciting part of the world that was conducive to our adventurous lifestyle.

While sailing from Panama to Fiji, we became accustomed to moving swiftly in order to stay ahead of the hurricane season. We were concerned that we’d be restless by the end of six months in one single country, but our time in New Zealand flew by and soon we were provisioned and making headway for Australia. The Tasman Sea has a reputation for being unforgiving, but we waited for the right weather and were rewarded with pleasant conditions. Tayrona sailed into Australian waters with a heavy heart, knowing that landfall would mark the end of this adventure. Late at night when we docked in Brisbane I was overcome by the indescribable experience of the last two years and the immeasurable personal growth we realized along the way. We spent an emotional month exploring Australia with my parents and gussying up Tayrona for sale.

Time in the real world seems to move in fast forward. Suddenly we were in Switzerland. Even more suddenly we were pregnant. And now here we are traveling through Croatia writing this account while our two year old daughter, Leonora, snores like an adorable diesel engine in the next room. The Swiss have made sure everything works seamlessly and are obnoxiously pleasant. While we don’t miss worrying about the anchor dragging in the night or the constant stream of repairs, we certainly miss our beloved Tayrona.

Switzerland definitely offers much to scratch our adventure itch. Abundant travel opportunities in Europe as well as the ability to climb, kitesurf, ski, and paraglide within sight of home makes it easy to put down roots without feeling constrained. We are happy to have found a dynamic, quality school full of dedicated educators where we feel fulfilled professionally.

Over the years we have fallen in love with the expat lifestyle and aim to keep exploring as long as we can. Now that kids have been added into the mix we feel obliged to share our love of exploration with them, and that includes the high seas. These experiences have not just been an adventure opportunity; they’ve caused us to grow in ways we could have never imagined. We can’t help but to continue our errant lifestyle, from which our blog’s name derives. At the moment we’re hunkered down, hatches dogged, weathering out Hurricane Toddler from the safety of a well-manicured Swiss harbor. But when the gale subsides and the seas call again, you can bet we’ll answer.

This article is available and can be accessed in Spanish here.