Grading Changes You Can Implement Now to Ensure Equity for All Learners

Among the myriad issues facing educators today – designing lessons for new environments, connecting with students, fulfilling curriculum expectations – teachers are tasked with the critical responsibility of providing our students with feedback on their learning. Students, like teachers, are experiencing emotional turmoil, constant change, and unpredictable futures. The anxiety around grades is only elevated by these circumstances, particularly when the variables in learning environments mean students aren’t always on a level field in their abilities to participate in classes, complete assignments or engage in all opportunities to demonstrate their learning. Amongst the learners in even one teacher’s class, there may be those who have personal devices, steady bandwidth and a quiet home-learning environment; for others, family members share one device, bandwidth can’t support video-streaming, and distractions abound. On average, there is likely some combination of the advantages and hindrances, and it can vary daily. How then do we, as educators, not only mitigate this added stress but, more importantly, implement grading practices which are just and equitable for all of our students?

Faced with this question, many teachers feel that they are constrained by policies and protocols, or that they are incapable of leading a systemic change across a school. But there are elements of practice explicitly within the teacher’s control that can have a direct impact on student learning and their well-being:

- First and foremost, consider the purpose of the grades which you assign. Are you serving the needs of each learner? Are you effectively utilizing formative assessment and ongoing feedback as well as appropriate summative evaluations to measure learning? A crucial component, “Formative assessment gives teachers continual information on student progress—information that supports decisions about how much and what kind of learning, support, and practice students need to reach the goal” (Greenstein, 2010). Across these areas, what practices in place do you have the autonomy to change?

- As an impactful initial consideration, and one which is a foundation of standards-based grading, eliminate the inclusion of behavior measures such as participation, effort, attitude, or other behaviors into student’s grades. While there is a perception that these motivate students to participate in class, for instance, now more than ever students are in positions wherein they may have no control over their schedule, internet access, or even events which influence their attitude and emotions. If a system is set up to measure this, you will be forced to decide: will I only reward those with all factors working in their favor? And conversely, will you penalize students who cannot participate (even if for the fact they missed an opportunity to earn those points) due to factors out of their control?

- Examine your assessments. Are they specifically reflective of the standard(s) you are measuring? Verify that your formative activities are appropriately aligned to your assessments. Consider the results: are they an average of mixed information, causing confusion as to what the results mean about what the student is ready to learn? Consider organizing your assessments according to the standards that each component measures and enter the feedback on each section as it specifically reflects that standard, rather than an average of the entire tool.

- Allow re-assessment. This is a common source of concern for teachers: it doesn’t seem “fair” to reward students who didn’t learn the skill or concept by a set deadline. Remember, our ultimate goal is for all students to learn, not to prevent the opportunity to learn due to our schedule by which they can be measured. Now more than ever, students are balancing complex responsibilities while attending to schoolwork: sharing household computers, restraints on quiet spaces to work, or even emotional stress. Accountability for learning remains the crucial factor, yet flexibility is essential. As shared by Tom Schimmer, “Teachers with a standards-based mindset still hold students accountable, but it’s a different working definition of accountability – a definition that views accountability not as punishment for undesirable behavior, but as responsibility for learning.” (Schimmer, 2014, p. 10).

- Applying Mastery Learning practices should not require overarching systems changes but, when done well, can dramatically enhance student learning. Ensure alignment between learning objectives, clear measures of mastery, and understanding by all students of the process towards achieving mastery. For deeper learning, check out this article on Getting Smart!

- Consider separating your gradebook into standards instead of assignments. Most Learning Management Systems make this cumbersome, but it is not impossible. Many of these programs are beginning to offer the choice to select standards-based organization over a points-based system, it just may require further exploration. Determine what you need from your grading platform to actualize this, and explore sites such as MasteryConnect, JumpRope or Kiddom.

- As you endeavor to understand your student’s progress, offer multiple ways to demonstrate learning. While this has always been an equitable practice, now more than ever we must recognize the complexities of our student’s current situations. Did they lose the internet while completing a Google quiz? Were they asked to babysit when you held a class discussion? The need for planned, strategic responses to our learner’s challenges must include alternative ways for their understanding to be measured.

- Plan for the unplanned. The name of the game this year (and perhaps future years?) is “unpredictable”. Grades simply cannot be designed to punish, apply consequences, or deepen the divide between teachers and learners due to distance learning. The simple fact is, there may be students this year whose faces you rarely, if ever, see on the other end of a synchronous meeting. We may not get to know the reason behind this challenge. With practices that focus on measuring learning free from the influence of behavior, we can, in some way, remove the constraints of these challenges to our primary goal of reaching every learner.

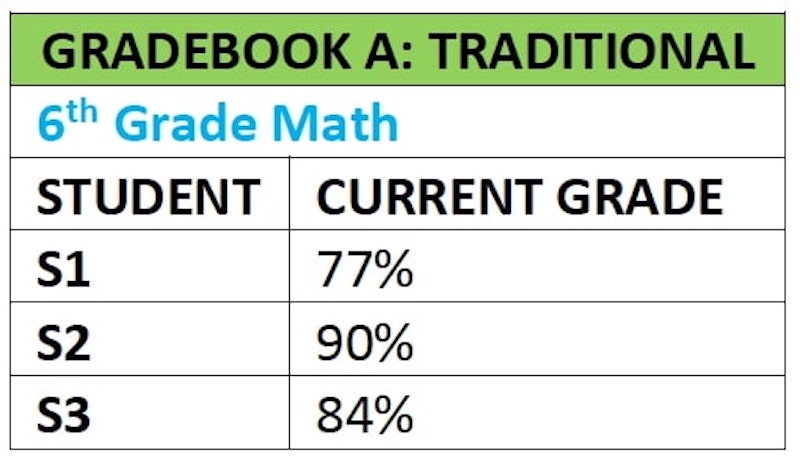

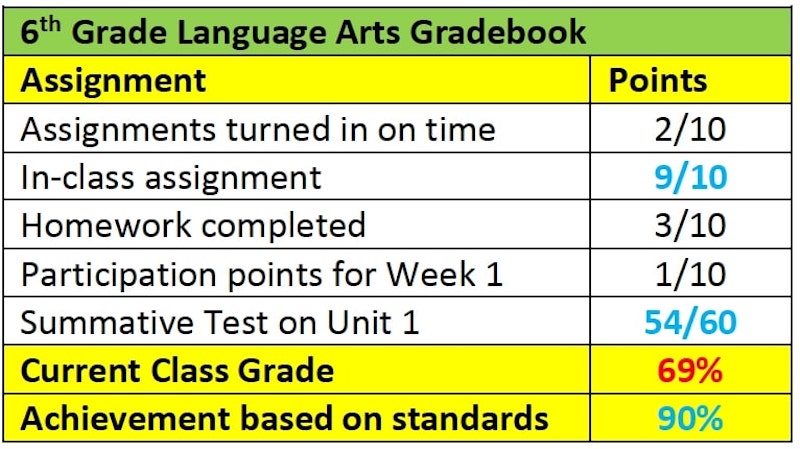

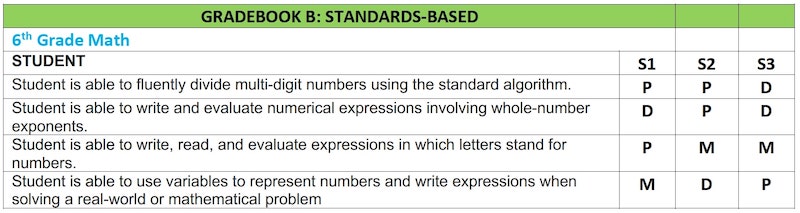

Standards-based grading can provide teachers with clear, specific, and actionable information around a student’s learning. Consider the sample from two different gradebooks below:

The teacher with Gradebook B has the opportunity to refer to the gradebook and understand that a student, or group of students, is still emerging or partially proficient on a specific standard. Instruction can be focused on this standard at the next immediate opportunity. In contrast, the teacher with Gradebook A sees a student with a 76% on a recent assessment and, unless the teacher has an outstanding memory, it is unclear whether the student may have incorrectly answered questions around one of a variety of standards being measured. The teacher would have to retrieve the exact assessment to be sure. Further, students themselves can benefit from the specificity of such information, particularly as they develop into the older grades such as Middle School. Learners are capable of recognizing that they possess a solid, proficient understanding of one particular skill or concept within a standard, but that they need to focus their efforts on those specific areas which they have not mastered – yet.

Equally as important as communication with learners, the clarity offered by standards-based grading enables parents to develop not only an accurate understanding of their child’s learning progression, but to recognize specific areas of focus around which they have an opportunity to contribute support. Communicating the depth and detail of information included in a standards-based grading system is well-received when parents realize the connection to the long-term benefits for their child. Perhaps increasingly beneficial as students develop into older grades and the natural teacher-parent communication path diminishes, parents become empowered to have direct information about what is occurring in the classroom. And, particularly as parents may be increasingly-active participants in the remote learning experience, conversations amongst teacher, student and parent(s) or caregiver(s) become acutely focused around meaningful, actionable information rather than, “how many assignments is my child missing?”. Whether a parent may themselves be capable of providing direct support – there’s no underlying expectation to give your Senior assistance in Calculus, for example! – the support structure for the student becomes inherently more explicit and, as a result, more effective.

Above all else, remember that your purpose is to ensure that each of your students learn the skills and concepts that you teach, and recognize that you have likely have ample opportunity to control your classroom practices by which you provide students feedback, including grades. We cannot control a student’s learning environment when they are at home; we cannot control the external influences to students’ lives such as trauma, emotional stress, absence of support structures and other factors. Yet we can ensure they learn in an equitable, supportive environment and receive clear, specific information about their learning when we design grading practices with the explicit measure of learning as the goal. Given the upheaval across the entire globe, this presents a tremendous opportunity to create positive change and proactively create a new “normal” for our collective future.

This article is available and can be accessed in Spanish here.

Schimmer, T. (2014). Grading with a standards-based mindset. AMLE Magazine, (2)4, 10-13.

Greenstein, L. (2010). What teachers really need to know about formative assessment. ASCD, Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/110017/chapters/The-Fundamentals-of-Formative-Assessment.aspx