Teaching and Learning in the 21st Century: Assessment

In my last article, I wrote about the importance of understanding the what and why of learning standards in education. In the article, I made this statement: “For all the negative talk about “teaching to the test,” educators sometimes forget that there is nothing wrong about teaching to the test–as long as it is a valid assessment of student learning!”

I’d like to unpack this idea some more. What are assessments, why do we use them, and what can we do to make them more informative as we shift our instructional practices from an outdated 19th Century model to an innovative and progressive model that reflects the needs of the 21st Century?

Let’s start with the “what.” What, after all, are assessments? To define assessments, it is worth unpacking what the word means. “Assessment” is, according to the dictionary, “the act of assessing” (dictionary.com). That definition, incidentally, is one that my fourth grade students would have told you is unacceptable; you should never define a thing by using its name! So we need to dig a bit deeper. If assessment is the act of assessing, then we need to know what it means to assess. The dictionary fortunately gives us a slightly better definition: “to estimate or judge the value, character, etc., of” something. Turning to the Online Dictionary of Etymology, a favourite tool of mine, as you may recall, we can learn the history of how this word has developed. From the early 15th Century, the word “assessment” has meant “to fix the amount (of a tax, fine, etc.),” originally from the frequentative of Latin assessus “a sitting by.” The entry goes on to explain that the one assessing was often a judge’s assistant and would, in the course of his duties, sit by the judge and declare the value of a thing.

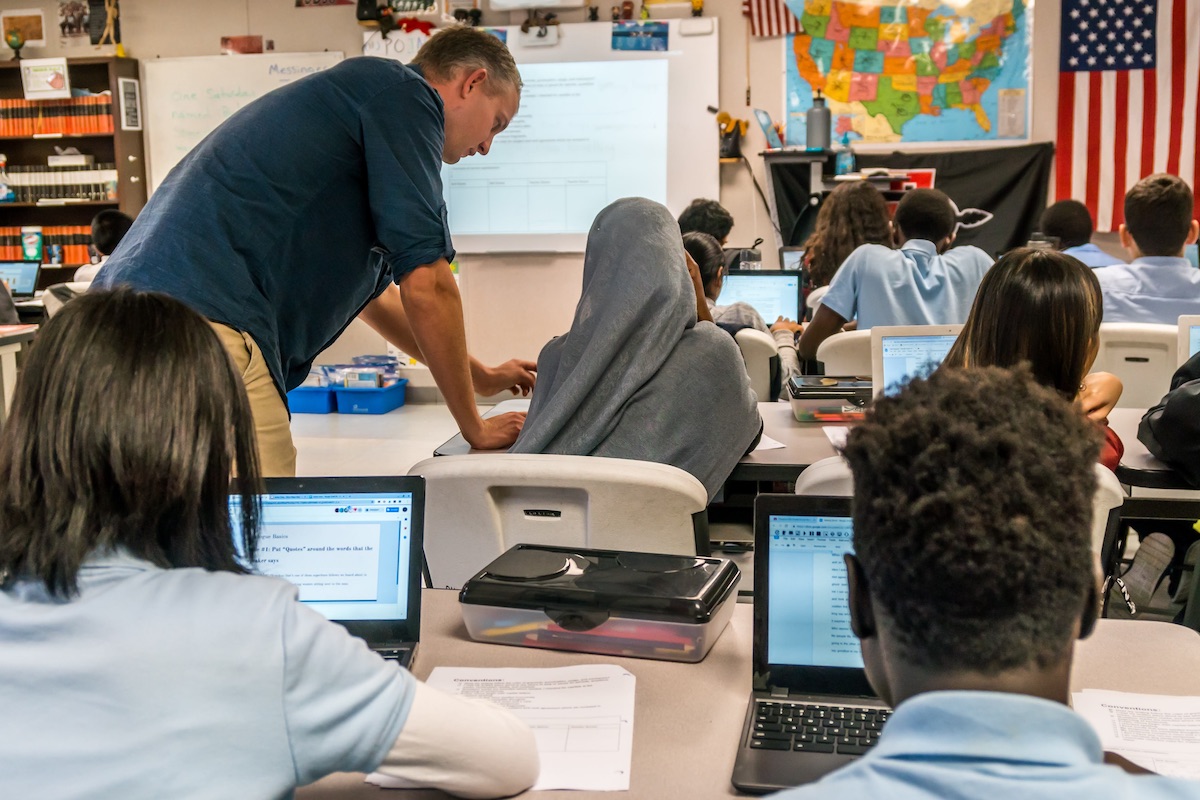

This notion of “sitting by” is intriguing to me. When we administer assessments to our students, are we sitting by them or are we taking the role of the judge, sitting above? I would argue that one shift we ought to make in this 21st Century environment is to apply the mindset of moving from the “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side” when teaching to assessing as well. Instead of administering tests, scoring them, and returning them to students with a score on the top of the page, we ought to view assessments as a tool that guides both us and our learners in the journey of education. Let us return to this in a moment.

So what is the thing that we are trying to estimate or judge the value, character, etc. of? In the field of education, we use assessments to attach a quantitative measure of competency to a qualitative state of growth. In other words, we use numbers to represent the quality of learning. It is essential that we understand this. As a former superintendent of mine often reminded us, “We do not define our students by their test scores.” Assessments are not an evaluation of the student but of the student’s learning. A kindergarten teacher may use an assessment to determine how many sight words a student can recognise; however, knowing a certain number of sight words isn’t the true purpose of the assessment. Rather, the number of recognised sight words is just one way of determining how well an emerging reader is able to access a text. A middle school technology teacher may assess a student’s research paper based on a rubric with specific criteria but is the focus really on the paper itself? No; it is on how well the student is able to access and use technology tools to create a final product. A high school math teacher may give an assessment on the use of quadratic functions but the reality is that very few of us ever use quadratic functions in our day-to-day lives. The assessment is really meant to help the teacher understand how well the student applies mathematical thinking to challenging problems. Consider the assessments you are using in your context and ask yourself, “What is it that I want to understand about my students and how will this assessment help me determine this?” If you cannot connect the two and the assessment is one you are selecting, it may be an indicator that you need to “teach to” a different test.

Let us now return to the idea of “sitting by” our students when we are assessing them. Like many educators today, I was taught in a system that loved scan-trons and bubble sheets. This format allowed teachers to quickly and accurately assign a numerical value to student learning. I would argue, however, that one of the great shortcomings of this method is what computer programmers refer to as GIGO. This acronym, which stands for “garbage in, garbage out,” reminds us that if the input is faulty, the output will be faulty. If the test format is inappropriate for the setting, the results will not provide the desired information. Additionally, multiple-choice, computer-scored assessments do not allow the teacher to see what their students are thinking and doing when they are engaging in a learning task. Fortunately, there is a better way.

Dr. Nicki Newton, author and math consultant, recognised the problem of uninformative assessments and presented a novel solution, which she described in her book, Math Running Records in Action. The best way to determine a student’s understanding of basic math concepts is to sit by the student, have them solve a problem, and make note of what they did and how they did it. In this approach, Dr. Newton is suggesting that teachers move from being the judge of student work and take on the role of assessor–of one “sitting by.” (The running record approach is common in elementary literacy classrooms, where teachers hold one-on-one conferences to have students read a passage aloud and makes notes on accuracy, fluency, expression, and comprehension.)

There are other ways that we can “sit by” our students when assessing their learning that don’t require the incredibly time-consuming one-on-one conference. We can provide performance tasks that include a portfolio of work that the students create and curate over time. We can offer collaborative assignments so that we can assess multiple students at once while still providing individualised, authentic feedback. Exit tickets, which often have just one to three items, can be used for students to quickly share understanding that the teacher can then review and sort in order to plan for future instruction.

This approach to assessment, while less efficient than multiple-choice, computer-scored tests, shifts the focus from the grade itself to the process of learning. By doing this, teachers are indeed going to be “teaching to the test” because the test is simply the progress-monitoring tool that shows them what their students understand or can do and where they need to go next. The test, or assessment, becomes a tool to plan and inform, rather than a hammer to judge and label.

This article is available and can be accessed in Spanish here.